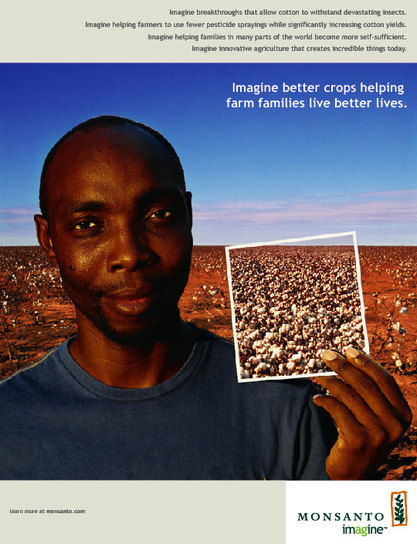

A wolf in sheep’s clothing: Monsanto’s public relations campaign. In North America, farmers often find themselves bullied into buying Monsanto’s genetically modified seeds or else sued for growing copyrighted Monsanto crop varieties after accidental cross-pollination from neighboring GMO fields. In India, the cycles of debt created by reliance on the company’s GMO seeds have led to a dramatic spike in farmer suicides in recent years.

The dangerous trend in our food system of power being concentrate in fewer and fewer [corporate] hands is something that cannot be adequately addressed by something as simple as signing a petition, though our signature may be a significant, small component of broad-based resistance. It is necessary to start somewhere. The current situation is one in which food travels vast distances along supply chains long enough to prevent us from ever knowing, most of the time, where exactly our food came from, how it was produced, what is in it, and what effect its production had on the people and the landscape of its place of origin. It is a destructive system in which short-term profit too often trumps the long-term well-being of land and people. It is an unjust arrangement in which, to quote author Mark Winne, “the poor get diabetes; the rich get local and organic.”

A few months back, Andy and I took a “faith in food” class at our church here in Vancouver. It was basically an in-depth look at the historical development of the industrial food system, the way it operates today, and its negative effects on people, animals, and ecosystems around the world. We also examined scripture in order to figure out our place as followers of Jesus in this global story that is unfolding. Given the mission of the church to participate in God’s restoration of the world, how are we to respond to the specific social, political, and economic circumstances that we find ourselves in right now? What does it look like to pursue justice and wholeness in the context of an economy in which many people cannot afford to buy healthy food; in which the way that we feed ourselves does not honor or protect our fellow creatures of the natural environment on which all of our lives ultimately depend? What does it mean to love our neighbors when some of them are losing their land or working under exploitative conditions to provide the food on our tables, and when others are literally being poisoned by the food that they eat?

In many ways, the time we spent praying, thinking, and talking about these issues raised more questions than answers and brought us to the realization that the simple act of eating has become fraught with complex ethical and practical problems. But we also reached clarity and consensus around the fact that seeking justice in the food system—which is hardly separable from environmental or economic justice overall—is among the most pressing moral concerns of our day. Responding to it is a task that we as Christians cannot afford to ignore.

Thus, you have this blog before you. A blog will not save the world, but perhaps it can be the start of an important conversation, one that will build community and build momentum around living more justly and compassionately in a world where it is very hard to live well. As Wendell Berry, that octogenarian farmer-poet from Kentucky, has said, “Better than any argument is to rise at dawn and pick dew-wet red berries in a cup.” So in addition to writing, I hope to get my hands dirty growing some food over the next few months, and doing what I can to support local farmers instead of corporate supply chains. These are small acts that will be done imperfectly, but it is a start, and I will not be going about it alone.