Living “simply” doesn’t mean I’ve conquered that internal drive to pursue comfort by acquiring more. I realized the other day that when I think of my home country, for example, what often come to mind are the products that I miss. Jamba Juice. Peppermint mochas from Starbucks. Scented body wash. Comfortable furniture. And I suppose that’s not bad in itself, but why are those the things that come to mind when I’m feeling tired and discouraged? The other day I thought about wandering around the supermarket in my hometown and just the idea of leisurely browsing aisle after aisle of specialty foods in air-conditioned comfort with endless options and variety and a massive supply that never runs out sounded so good to me. I found myself daydreaming about just walking around there, not even buying anything. I mean, I like eating hummus and cheese and Fritos and all those things you just can’t get easily in Northern India, but even just shopping for them sounds comforting and familiar. The idea of the glossy lights and colors of the cosmetics section brings up similar feelings, even though I hardly own any makeup and am usually turned off by all of the advertising when I’m actually near it.

The Kingdom of God that Jesus is constantly talking about in the Gospels encompasses God’s vision for humanity to enjoy freedom, justice, mercy, peace, and inclusion in a community of love. In first century Palestine, the powers of evil which killed Jesus were embodied in the brute force of Rome and the religious authority of the Pharisees, whose legalistic, judgmental, and top-down religious system was set against everything his Kingdom stood for. In the same way, perhaps a big part of the Empire and religious establishment of our day is the soulless system of materialism, consumption, and ever-increasing wealth in which we are all enmeshed in some way or another, whether we realize it or not. Globally, this system values profits and products over people, exploits the poor and vulnerable with low wages and unsafe working conditions to create cheap, mass-produced commodities for the wealthy, and often involves the degradation of the natural world in order to create these disposable items that will one day become trash in a landfill.

And this impersonal system of commerce not only harms our neighbors—it eats away at our own souls as well. We consume to feel beautiful, important, safe, impressive, comforted, or just distracted from the needs of the world and the inner turmoil of our souls. Maybe we even pursue more and more external stimuli and experiences and possessions in order to be distracted from the gaping fear that if we ever stopped to look too deeply within ourselves we might find that we are not who we present ourselves to be, or—worse— that there is nothing of substance within us at all. There are a lot of buoyant memories from my younger years of happily buying a new outfit or accessory or CD and feeling a sense of fulfillment with the new appearance or experience I was instantly gratified with, but I remember too that none of those times ever felt like the last time I would need another stick of eyeliner or some new music. There was always more out there that I didn’t have, and as trends changed I would inevitably want more or at least something different than what I already had. Seasonal fashion and planned obsolescence and insecurity in who we are can fuel continuous consumption that makes us feel like we’re on the way to being a happier person by satiating ourselves or achieving a certain image, but we never seem to arrive. I still find this mistaken belief system at work in my heart.

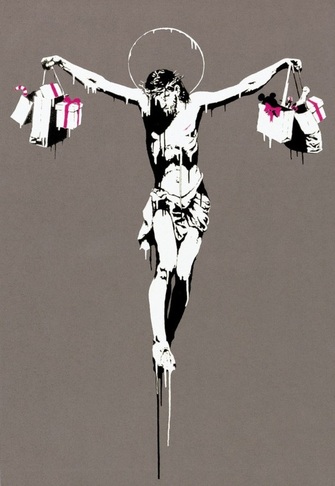

As I consider this unorthodox but rather profound image of Jesus on the cross, the thought strikes me that this carefully-cultivated superficiality needs to be crucified before authentic life can grow in its place.