We are living in wild times. Our current president–one who was voted into office with the overwhelming support of evangelical Christians–is a man whose disregard for the lives of women, immigrants, people of color, and Americans who live in poverty is being codified into national policies and laws which have real and brutal effects on the lives of the most marginalized in our society. The hundreds of families being separated at the border, the denial of refugee protection to women fleeing domestic violence, and the erasure of women from influential positions in government are just a few of the most recent, glaring examples of this.

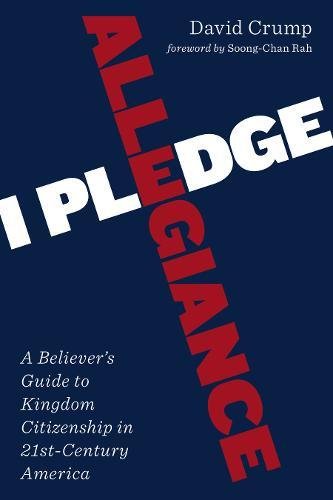

Bombarded as we are with one situation after another in which the laws and actions of our government come into conflict with the teachings and example of Jesus, David Crump’s book, I Pledge Allegiance, strikes me as a timely read for American Christians. Crump boldly grapples with the ethics of how to live faithfully as followers of Jesus under the earthly governance of a nation state–and explores the limits of our allegiance when the Kingdom of God and the United States of America come into conflict.

Last month, I reviewed Crump’s book for the Englewood Review of Books. Here’s an excerpt:

I grew up Southern Baptist in a small town in Texas. I still remember singing the fight songs of each branch of the military during patriotic worship services celebrating the Fourth of July or Veterans’ Day, and pledging allegiance to both the Christian and American flags that hung in the sanctuary. According to David Crump, this display of Christian nationalism demonstrates that rather than being immersed in the gospel Jesus preached, I was instead awash in the kind of dangerous “civil religion” that characterizes much of the American church today.

In I Pledge Allegiance: A Believer’s Guide to Kingdom Citizenship in 21st-Century America, Crump sets out to write an ethics book that addresses “the social issues confronting today’s church,” roots “its analysis in biblical interpretation,” and takes “the teaching of Jesus as its starting point” (5). The result is a hard-hitting treatise on faithful citizenship in the kingdom of God that addresses the meaning and political implications of that kingdom…

You can read the rest over at the Englewood Review of Books.