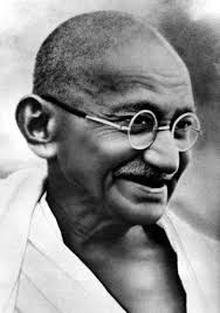

“[A]s my contact with real Christians increased, I could see that the Sermon on the Mount was the whole Christianity for him who wanted to live the Christian life… it seems to me that Christianity has yet to be lived.” –Gandhi, as quoted by Stanley Hauerwas in Performing the Faith, 2004

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

I feel convicted by the words of Gandhi on the subject of the Sermon on the Mount and the pursuit of the Kingdom of God. It occurs to me that in many ways, the way of Jesus is “yet to be lived” in my own life. I haven’t yet attained the courage to free myself from anger, fear, and desire to retaliate in the face of mistreatment and violence.

I am walking down the side of the road alone. A motorcycle brushes past me from behind, much too close for comfort. Two men look back to stare at me, the foreign woman walking alone. My mind immediately begins to play through the hypothetical situations of what I would have done if they had actually touched me, what I will do if they stop to cause any trouble. My eyes fall to a brick lying in the dust ahead of me. I picture myself picking up the brick and throwing it at them with full force.

In the sea of people leaving the park, a man walks past me in the opposite direction and gropes me. I wheel around and hit him in the back with my water bottle. No physical harm done to him (unfortunately, I think to myself), but I know that it would have been my knuckles into his back if he had been any closer—my reaction was instinctive and automatic.

Crossing the street with my husband on the way to a friend’s house, a man cat-calls at me and proceeds to make animal noises. I’ve had enough of this kind of disrespect. We walk swiftly toward him (and the rest of the day laborers he’s sitting with) and confront him in Hindi: “Are you an animal? What are you making those noises for?” Before I know it, there’s a hand on my shoulder and a middle-class Indian friend who lives nearby is taking my place in front of the man scolding him about his harassment. But before she’s finished, another middle-class man—a total stranger—has noticed this gathering of important-looking people confronting some poor, low-caste riff-raff from the villages and steps forward to hit the man without even knowing what has happened (or caring to ask questions). At this point A. and I both move forward to stop the violence, but it’s too late. Policemen pull up on their motorbikes out of nowhere and similarly enter the fray, beating first and asking question later. We try to pull them back from the man, saying that there’s no need to beat him; nothing has really happened. What began as our confronting a man about his dehumanizing treatment of women has rapidly turned into the wealthy, powerful people ganging up on the poor—who, due to malnutrition and hard manual labor, are literally half their size. The man is suddenly clasping his hands and appealing to me for forgiveness—but of course, this is no heart transformation. Fear has driven out any chance of reason or reflection. He fears for his life under the police officer’s baton–the same batons that threatened women and children at the protest rally a few weeks ago. This was not a situation I had intended to create. I wasn’t happy about it. And I didn’t feel any vindication in my dehumanization being paid for with his. The same system of domination and violence was oppressing us both, and we had both become pawns in its game.

If I don’t commit violent acts but only fantasize about them in my head, then am I really free of violence? And if I don’t use physical force, but seek to demean, insult, and control others with hateful words, then can I really claim to be overcoming evil with good? Am I seeking the transformation of my own heart and the redemption of my enemy when I respond to their aggression in kind?

These stressful situations bring out parts of my inner self that might remain hidden forever in a different environment—say, my hometown. I am forced to face the limits of my faith, and the gap between my stated convictions and my actions and ingrained reflexes. It’s one thing to talk about the Sermon on the Mount. It’s quite another to find creative ways of loving my enemies, especially when they outnumber me or have superior social position and physical strength. But surely Jesus was aware of these sorts of situations when he charged his hearers to repay evil with good and to love their enemies. I’m sure that Roman soldiers had similar tactics and maybe even similar weapons when they came down on Jewish peasants in occupied Palestine during Jesus’ days. And even sexual violence is certainly nothing new. But creativity, and self-restraint, and even a willingness to suffer (NOT to be confused with passive acceptance of abuse) certainly take a lot of practice, and ultimately, as Gandhi says, they can be put into practice only “by the power and grace of God.”

I don’t know all of the answers, but in the active “satyagraha” (“the Force which is born of Truth or Love”) resistance that Gandhi taught and practiced—the same method of active-nonviolent resistance that inspired Martin Luther King’s “soul force” movement in our own country fifty years ago—I am challenged to pursue and experiment with Jesus’ teaching under the assumption that it is not only possible, but necessary as the only way to resist the cycles of violence in our world rather than reinforcing and becoming a part of them.

May it not be said of our lives that we have left the way of Jesus untried.